Archaeology News: 2025.08.31

Biblical Archaeological Society News

- Posted on Thursday August 07, 2025

Painting from the tomb of Nebamun showing a cat catching birds. Courtesy of the British Museum.

Despite their stereotypically aloof attitude, cats are so popular today that they have been photographed the world over, are the stars of YouTube videos and have even been provided sanctuary at an archaeological site. When were cats domesticated? According to a 2014 study led by Wim Van Neer of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, cats may have been domesticated in ancient Egypt much earlier than previously thought.

Cats are traditionally believed to have been domesticated in Egypt during the Middle Kingdom (c. 1950 B.C.E.). Famously devoted to these furry creatures—calling them miw onomatopoetically—the Egyptians mummified deceased cats and depicted them in paintings and sculptures. Cats were associated with a number of Egyptian deities, including Bastet, the goddess of fertility and protector of women in childbirth.

FREE ebook: Ancient Israel in Egypt and the Exodus.

Email(Required)

REQUEST FREE BOOK

DOWNLOAD EBOOK

Excavations conducted at Hierakonpolis, the capital of Upper Egypt during the Predynastic period, yielded evidence suggesting that cats were tamed as early as the fourth millennium B.C.E. The skeleton of a jungle cat discovered in an elite cemetery dated to c. 3700 B.C.E. showed signs of a ... Continue Reading...

Painting from the tomb of Nebamun showing a cat catching birds. Courtesy of the British Museum.

Despite their stereotypically aloof attitude, cats are so popular today that they have been photographed the world over, are the stars of YouTube videos and have even been provided sanctuary at an archaeological site. When were cats domesticated? According to a 2014 study led by Wim Van Neer of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, cats may have been domesticated in ancient Egypt much earlier than previously thought.

Cats are traditionally believed to have been domesticated in Egypt during the Middle Kingdom (c. 1950 B.C.E.). Famously devoted to these furry creatures—calling them miw onomatopoetically—the Egyptians mummified deceased cats and depicted them in paintings and sculptures. Cats were associated with a number of Egyptian deities, including Bastet, the goddess of fertility and protector of women in childbirth.

FREE ebook: Ancient Israel in Egypt and the Exodus.

Email(Required)

REQUEST FREE BOOK

DOWNLOAD EBOOK

Excavations conducted at Hierakonpolis, the capital of Upper Egypt during the Predynastic period, yielded evidence suggesting that cats were tamed as early as the fourth millennium B.C.E. The skeleton of a jungle cat discovered in an elite cemetery dated to c. 3700 B.C.E. showed signs of a ... Continue Reading... - Posted on Sunday July 06, 2025

“After the conclusion of the treaty they left with their families and chattels, not fewer than two hundred and forty thousand people, and crossed the desert into Syria. Fearing the Assyrians, who dominated over Asia at that time, they built a city in the country which we now call Judea. It was large enough to contain this great number of men and was called Jerusalem.”

–Josephus, Against Apion 1.73.7, quoting Manetho’s Aegyptiaca

Excavations at Tel Habuwa, thought to be ancient Tjaru, reveal evidence of the expulsion of the Hyksos by Ahmose I at the end of the Second Intermediate Period.

In the Second Intermediate Period (18th–16th centuries B.C.E.), towards the end of the Middle Bronze Age, the West Asian (Canaanite) Hyksos controlled Lower (Northern) Egypt. In the 16th century, Ahmose I overthrew the Hyksos and initiated the XVIII dynasty and the New Kingdom of Egypt.

Archaeological discoveries at Tel Habuwa (also known as Tell el-Habua or Tell-Huba), a site associated with ancient Tjaru (Tharo), shed light on Ahmose’s campaign. A daybook entry in the famous Rhind Mathematical Papyrus notes that Ahmose seized control of Tjaru before laying siege the Hyksos at their capital in Avaris.

Excavations at the site, located two miles east of the Suez Canal, have uncovered evidence of battle wounds on skeletons discovered in two-story administrative structures dating to the Hyksos and New Kingdom occupations. The site showed evidence of burned buildings, as well as massive New Kingdom grain silos that would have been able to feed a large number of Egyptian troops. After Ahmose took the city and defeated the Hyksos, he expanded the town and built several nearby forts to protect Egypt’s eastern border. Tjaru was first discovered in 2003, but until now, the excavation only uncovered the New Kingdom military fort and silos. This new discovery confirms a decisive moment in the expulsion of the Hyksos previously known from textual sources.

Tomb painting from Beni Hasan, Egypt. A figure named Abisha and identified by the title Hyksos leads brightly garbed Semitic clansmen into Egypt to conduct trade. Dating to about 1890 B.C.E., the painting is preserved on the wall of a tomb carved into cliffs overlooking the Nile at Beni Hasan, about halfway between Cairo and Luxor. In the early second millennium B.C.E., numerous Asiatics infiltrated Egypt, some of whom eventually gained control over Lower Egypt for about a century and a half. The governing class of these people became known as the Hyksos, which means “Rulers of Foreign Lands.”

The Hyksos are well known from ancient texts, and their expulsion was recorded in later ancient Egyptian historical narratives. The third-century B.C.E. Egyptian historian Manetho–whose semi-accurate histories stand out as valuable resources for cataloging Egyptian kingship–wrote of the Hyksos’ violent entry into Egypt from the north, and the founding of their monumental capital at Avaris, a city associated with the famous excavations at Tell ed-Dab’a. After the Hyksos were expelled from Egypt, Manetho reports that they wandered the desert before establishing the city of Jerusalem.

FREE ebook: Ancient Israel in Egypt and ... Continue Reading...

“After the conclusion of the treaty they left with their families and chattels, not fewer than two hundred and forty thousand people, and crossed the desert into Syria. Fearing the Assyrians, who dominated over Asia at that time, they built a city in the country which we now call Judea. It was large enough to contain this great number of men and was called Jerusalem.”

–Josephus, Against Apion 1.73.7, quoting Manetho’s Aegyptiaca

Excavations at Tel Habuwa, thought to be ancient Tjaru, reveal evidence of the expulsion of the Hyksos by Ahmose I at the end of the Second Intermediate Period.

In the Second Intermediate Period (18th–16th centuries B.C.E.), towards the end of the Middle Bronze Age, the West Asian (Canaanite) Hyksos controlled Lower (Northern) Egypt. In the 16th century, Ahmose I overthrew the Hyksos and initiated the XVIII dynasty and the New Kingdom of Egypt.

Archaeological discoveries at Tel Habuwa (also known as Tell el-Habua or Tell-Huba), a site associated with ancient Tjaru (Tharo), shed light on Ahmose’s campaign. A daybook entry in the famous Rhind Mathematical Papyrus notes that Ahmose seized control of Tjaru before laying siege the Hyksos at their capital in Avaris.

Excavations at the site, located two miles east of the Suez Canal, have uncovered evidence of battle wounds on skeletons discovered in two-story administrative structures dating to the Hyksos and New Kingdom occupations. The site showed evidence of burned buildings, as well as massive New Kingdom grain silos that would have been able to feed a large number of Egyptian troops. After Ahmose took the city and defeated the Hyksos, he expanded the town and built several nearby forts to protect Egypt’s eastern border. Tjaru was first discovered in 2003, but until now, the excavation only uncovered the New Kingdom military fort and silos. This new discovery confirms a decisive moment in the expulsion of the Hyksos previously known from textual sources.

Tomb painting from Beni Hasan, Egypt. A figure named Abisha and identified by the title Hyksos leads brightly garbed Semitic clansmen into Egypt to conduct trade. Dating to about 1890 B.C.E., the painting is preserved on the wall of a tomb carved into cliffs overlooking the Nile at Beni Hasan, about halfway between Cairo and Luxor. In the early second millennium B.C.E., numerous Asiatics infiltrated Egypt, some of whom eventually gained control over Lower Egypt for about a century and a half. The governing class of these people became known as the Hyksos, which means “Rulers of Foreign Lands.”

The Hyksos are well known from ancient texts, and their expulsion was recorded in later ancient Egyptian historical narratives. The third-century B.C.E. Egyptian historian Manetho–whose semi-accurate histories stand out as valuable resources for cataloging Egyptian kingship–wrote of the Hyksos’ violent entry into Egypt from the north, and the founding of their monumental capital at Avaris, a city associated with the famous excavations at Tell ed-Dab’a. After the Hyksos were expelled from Egypt, Manetho reports that they wandered the desert before establishing the city of Jerusalem.

FREE ebook: Ancient Israel in Egypt and ... Continue Reading... - Posted on Sunday June 29, 2025

A recent study on mitochondrial DNA revealed that the female line of Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry closely resembles that of Southern and Western Europe, rather than the ancient Near East, as many scholars proposed in the past.

Ashkenazim, a Jewish group who migrated to Central and Eastern Europe, make up the majority of the world’s Jewish population today.

A recent article in Nature Communications discusses the results of the mtDNA tests. The article, written by a team of scientists led by the University of Huddersfield’s Martin B. Richards, includes the following in its abstract:

Like Judaism, mitochondrial DNA is passed along the maternal line. Its variation in the Ashkenazim is highly distinctive, with four major and numerous minor founders … we show that all four major founders, ~40% of Ashkenazi mtDNA variation, have ancestry in prehistoric Europe, rather than the Near East or Caucasus. Furthermore, most of the remaining minor founders share a similar deep European ancestry. Thus the great majority of Ashkenazi maternal lineages were not brought from the Levant, as commonly supposed, nor recruited in the Caucasus, as sometimes suggested, but assimilated within Europe. These results point to a significant role for the conversion of women in the formation of Ashkenazi communities, and provide the foundation for a detailed reconstruction of Ashkenazi genealogical history.

FREE ebook: Israel: An Archaeological Journey. Sift through the storied history of ancient Israel.

First Name:*

Last Name:*

Email Address: *

* Indicates a required field.

SUBMIT

If you don’t want to receive the Bible History Daily newsletter, uncheck this box.

Earlier DNA tests performed on male chromosomes in Jewish communities generally reveal Near Eastern DNA patterns. Population migration and conversion to Judaism may have led to the growth of the Ashkenazi population. Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry may, in fact, stem from the Jewish community in the early Roman Empire. The authors write that “a substantial Jewish community was present in Rome from at least the mid-second century BCE, maintaining links to Jerusalem and numbering 30,000–50,000 by the first half of the first century C.E. By the end of the first millennium CE, Ashkenazi communities were historically visible along the Rhine valley in Germany.”

Read more in Nature Communications.

This article was first published in Bible History Daily on October 10, 2013

Related reading in Bible History Daily

Who Were the Minoans?

DNA Suggests Early Jewish Links with Africa

Jews and Arabs Descended from Canaanites

Become a BAS All-Access Member Now!

Read Biblical Archaeology Review online, explore 50 years of BAR, watch videos, attend talks, and more

The post Ashkenazi Jewish Ancestry Confirmed European by mtDNA Tests appeared first on Biblical Archaeology Society.

Continue Reading...

A recent study on mitochondrial DNA revealed that the female line of Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry closely resembles that of Southern and Western Europe, rather than the ancient Near East, as many scholars proposed in the past.

Ashkenazim, a Jewish group who migrated to Central and Eastern Europe, make up the majority of the world’s Jewish population today.

A recent article in Nature Communications discusses the results of the mtDNA tests. The article, written by a team of scientists led by the University of Huddersfield’s Martin B. Richards, includes the following in its abstract:

Like Judaism, mitochondrial DNA is passed along the maternal line. Its variation in the Ashkenazim is highly distinctive, with four major and numerous minor founders … we show that all four major founders, ~40% of Ashkenazi mtDNA variation, have ancestry in prehistoric Europe, rather than the Near East or Caucasus. Furthermore, most of the remaining minor founders share a similar deep European ancestry. Thus the great majority of Ashkenazi maternal lineages were not brought from the Levant, as commonly supposed, nor recruited in the Caucasus, as sometimes suggested, but assimilated within Europe. These results point to a significant role for the conversion of women in the formation of Ashkenazi communities, and provide the foundation for a detailed reconstruction of Ashkenazi genealogical history.

FREE ebook: Israel: An Archaeological Journey. Sift through the storied history of ancient Israel.

First Name:*

Last Name:*

Email Address: *

* Indicates a required field.

SUBMIT

If you don’t want to receive the Bible History Daily newsletter, uncheck this box.

Earlier DNA tests performed on male chromosomes in Jewish communities generally reveal Near Eastern DNA patterns. Population migration and conversion to Judaism may have led to the growth of the Ashkenazi population. Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry may, in fact, stem from the Jewish community in the early Roman Empire. The authors write that “a substantial Jewish community was present in Rome from at least the mid-second century BCE, maintaining links to Jerusalem and numbering 30,000–50,000 by the first half of the first century C.E. By the end of the first millennium CE, Ashkenazi communities were historically visible along the Rhine valley in Germany.”

Read more in Nature Communications.

This article was first published in Bible History Daily on October 10, 2013

Related reading in Bible History Daily

Who Were the Minoans?

DNA Suggests Early Jewish Links with Africa

Jews and Arabs Descended from Canaanites

Become a BAS All-Access Member Now!

Read Biblical Archaeology Review online, explore 50 years of BAR, watch videos, attend talks, and more

The post Ashkenazi Jewish Ancestry Confirmed European by mtDNA Tests appeared first on Biblical Archaeology Society.

Continue Reading... - Posted on Thursday June 26, 2025

In 2017 scholars Eshbal Ratson and Jonathan Ben-Dov of the Department of Bible Studies at the University of Haifa published one of the last two remaining Dead Sea Scrolls in their article “A Newly Reconstructed Calendrical Scroll from Qumran in Cryptic Script” in the Journal of Biblical Literature (Winter 2017).

For more than a year, the scholars diligently pieced together 62 Dead Sea Scroll fragments, on which there was writing in code. Ratson and Ben-Dov deciphered the code on the reconstructed scroll, called Scroll 4Q324d, and revealed that the scroll describes a 364-day calendar used by the Qumran community that lived in the Judean Desert. This Qumran calendar gives us insight into how the community organized the seasons and religious festivals, and it sheds light on scribal customs.

A portion of the recently deciphered Dead Sea Scroll 4Q324d containing a 364-day calendar used by the Qumran community in the Judean Desert. Photo: Courtesy of the University of Haifa.

The Dead Sea Scrolls—considered the greatest manuscript find of all time—were the writings of a small Jewish sect living at the site of Khirbet Qumran near the Dead Sea. Dating between 250 B.C.E. and 68 C.E., the scrolls contain both Hebrew Bible texts and texts that describe the particular beliefs and practices of this Qumran community, which called itself the Yahad (“together”).

FREE ebook: The Dead Sea Scrolls: Discovery and Meaning. What the Dead Sea Scrolls teach about Judaism and Christianity.

Email(Required)

REQUEST FREE BOOK

... Continue Reading...

In 2017 scholars Eshbal Ratson and Jonathan Ben-Dov of the Department of Bible Studies at the University of Haifa published one of the last two remaining Dead Sea Scrolls in their article “A Newly Reconstructed Calendrical Scroll from Qumran in Cryptic Script” in the Journal of Biblical Literature (Winter 2017).

For more than a year, the scholars diligently pieced together 62 Dead Sea Scroll fragments, on which there was writing in code. Ratson and Ben-Dov deciphered the code on the reconstructed scroll, called Scroll 4Q324d, and revealed that the scroll describes a 364-day calendar used by the Qumran community that lived in the Judean Desert. This Qumran calendar gives us insight into how the community organized the seasons and religious festivals, and it sheds light on scribal customs.

A portion of the recently deciphered Dead Sea Scroll 4Q324d containing a 364-day calendar used by the Qumran community in the Judean Desert. Photo: Courtesy of the University of Haifa.

The Dead Sea Scrolls—considered the greatest manuscript find of all time—were the writings of a small Jewish sect living at the site of Khirbet Qumran near the Dead Sea. Dating between 250 B.C.E. and 68 C.E., the scrolls contain both Hebrew Bible texts and texts that describe the particular beliefs and practices of this Qumran community, which called itself the Yahad (“together”).

FREE ebook: The Dead Sea Scrolls: Discovery and Meaning. What the Dead Sea Scrolls teach about Judaism and Christianity.

Email(Required)

REQUEST FREE BOOK

... Continue Reading... - Posted on Sunday June 01, 2025

What happened to the Canaanites? DNA sequencing was conducted on five skeletons from Canaanite Sidon, including this one. The results indicate that there is a “genetic continuity” between the Canaanites at Sidon and the modern Lebanese. Photo: Courtesy of Claude Doumet-Serhal.

What happened to the Canaanites? Researchers conducted DNA sequencing on ancient Canaanite skeletons and have determined where the Canaanites’ descendants can be found today.

The Canaanites were a Semitic-speaking cultural group that lived in Canaan (comprising Lebanon, southern Syria, Israel and Transjordan) beginning in the second millennium B.C.E. and wielded influence throughout the Mediterranean.

In the Hebrew Bible, the Canaanites are described as inhabitants of Canaan before the arrival of the Israelites (e.g., Genesis 15:18–21, Exodus 13:11). Little of the Canaanites’ textual records remain, perhaps because they used papyrus instead of the more durable clay for writing. Much of the Canaanites’ history is reconstructed through the writings of contemporary peoples in addition to archaeological examinations of the material record.

FREE eBook: Life in the Ancient World. Craft centers in Jerusalem, family structure across Israel and ancient practices—from dining to makeup—through the Mediterranean world.

Email(Required)

REQUEST FREE BOOK

DOWNLOAD EBOOK

Marc Haber, Claude Doumet-Serhal, Christiana Scheib and a team of 13 other scientists recently published their ... Continue Reading...

What happened to the Canaanites? DNA sequencing was conducted on five skeletons from Canaanite Sidon, including this one. The results indicate that there is a “genetic continuity” between the Canaanites at Sidon and the modern Lebanese. Photo: Courtesy of Claude Doumet-Serhal.

What happened to the Canaanites? Researchers conducted DNA sequencing on ancient Canaanite skeletons and have determined where the Canaanites’ descendants can be found today.

The Canaanites were a Semitic-speaking cultural group that lived in Canaan (comprising Lebanon, southern Syria, Israel and Transjordan) beginning in the second millennium B.C.E. and wielded influence throughout the Mediterranean.

In the Hebrew Bible, the Canaanites are described as inhabitants of Canaan before the arrival of the Israelites (e.g., Genesis 15:18–21, Exodus 13:11). Little of the Canaanites’ textual records remain, perhaps because they used papyrus instead of the more durable clay for writing. Much of the Canaanites’ history is reconstructed through the writings of contemporary peoples in addition to archaeological examinations of the material record.

FREE eBook: Life in the Ancient World. Craft centers in Jerusalem, family structure across Israel and ancient practices—from dining to makeup—through the Mediterranean world.

Email(Required)

REQUEST FREE BOOK

DOWNLOAD EBOOK

Marc Haber, Claude Doumet-Serhal, Christiana Scheib and a team of 13 other scientists recently published their ... Continue Reading...

![]()

News from the American Journal of Archaeology

- Posted on Tuesday June 17, 2025

The post Brunilde Sismondo Ridgway (1929–2024) appeared first on American Journal of Archaeology. Continue Reading...

- Posted on Tuesday June 17, 2025

The post Erratum appeared first on American Journal of Archaeology. Continue Reading...

- Posted on Tuesday June 17, 2025

The Gulf of Manfredonia, on the northern Adriatic coast of Apulia, has been the site of many settlements over nearly three millennia. In this article, we write the environmental history of the south-facing Salapia Lagoon and three towns—Salpia vetus, Salapia, and Salpi—bringing together archaeological, paleoenvironmental, climatological, and textual evidence. Each town manifested strategies to thrive in a wetland environment as a center for trade, administration, and logistics. Each also experienced periods of progressive decline caused by the overexploitation of lagoon resources and environmental challenges. We argue that the micromobility of these settlements served as a repeated and productive strategy to overcome insalubrity and precarity, ensuring the continuity of lagoon life. This case study reveals patterns informative for expanding current conversations around climate migration and how best to manage dynamic wetland environments. The post Communities on the Move in Coastal Apulia (Southern Italy), 10th Century BCE to 17th Century CE: 2,600 Years of Human-Environment Coevolution at Salapia appeared first on American Journal of Archaeology. Continue Reading...

- Posted on Tuesday June 17, 2025

The post Un public ou des publics? La réception des spectacles dans le monde romain entre pluralité et unanimité appeared first on American Journal of Archaeology. Continue Reading...

- Miscellaneous Objects: Final Publications from the Danish-German Jerash Northwest Quarter Project VIPosted on Tuesday June 17, 2025

The post Miscellaneous Objects: Final Publications from the Danish-German Jerash Northwest Quarter Project VI appeared first on American Journal of Archaeology. Continue Reading...

![]()

![]()

Roman Archaeology Blog

- Posted on Sunday April 07, 2024

A large Roman villa was uncovered in Oxfordshire. Credit: Red River Archaeology GroupThe complex was adorned with intricate painted plaster and mosaics and housed a collection of small, tightly coiled lead scrolls. The Red River Archaeology Group (RRAG), the organization responsible for coordinating the excavation, announced in a press release that these elements suggest that the site may have been used for rituals or pilgrimages.Francesca Giarelli, the Red River Archaeology Group project officer and the site director, told CNN that the villa likely had multiple levels. The Roman villa complex, spanning an impressive 1,000 square meters (or 10,800 square feet) on its ground floor alone, was likely a prominent landmark visible from miles away.“The sheer size of the buildings that still survive and the richness of goods recovered suggest this was a dominant feature in the locality if not the wider landscape,” says Louis Stafford, a senior project manager at RRAG, in the statement.Read the rest of this article... Continue Reading...

A large Roman villa was uncovered in Oxfordshire. Credit: Red River Archaeology GroupThe complex was adorned with intricate painted plaster and mosaics and housed a collection of small, tightly coiled lead scrolls. The Red River Archaeology Group (RRAG), the organization responsible for coordinating the excavation, announced in a press release that these elements suggest that the site may have been used for rituals or pilgrimages.Francesca Giarelli, the Red River Archaeology Group project officer and the site director, told CNN that the villa likely had multiple levels. The Roman villa complex, spanning an impressive 1,000 square meters (or 10,800 square feet) on its ground floor alone, was likely a prominent landmark visible from miles away.“The sheer size of the buildings that still survive and the richness of goods recovered suggest this was a dominant feature in the locality if not the wider landscape,” says Louis Stafford, a senior project manager at RRAG, in the statement.Read the rest of this article... Continue Reading... - Posted on Sunday April 07, 2024

Today, Smallhythe Place in Kent is best known as a bohemian rural retreat once owned by the Victorian actress Ellen Terry and her daughter Edy Craig. As this month’s cover feature reveals, however, the surrounding fields preserve evidence of much earlier activity, including a medieval royal shipyard and a previously unknown Roman settlement (below, first image). Our next feature comes from the heavy clays of the Humber Estuary, where excavations sparked by theconstruction of an offshore windfarm have opened a 40km transect through northern Lincolnshire, with illuminating results (below, second image). We then take a tour of Iron Age, Roman, and medieval Winchester, tracing its evolution into a regional capital and later a royal power centre.Read the rest of this article... Continue Reading...

Today, Smallhythe Place in Kent is best known as a bohemian rural retreat once owned by the Victorian actress Ellen Terry and her daughter Edy Craig. As this month’s cover feature reveals, however, the surrounding fields preserve evidence of much earlier activity, including a medieval royal shipyard and a previously unknown Roman settlement (below, first image). Our next feature comes from the heavy clays of the Humber Estuary, where excavations sparked by theconstruction of an offshore windfarm have opened a 40km transect through northern Lincolnshire, with illuminating results (below, second image). We then take a tour of Iron Age, Roman, and medieval Winchester, tracing its evolution into a regional capital and later a royal power centre.Read the rest of this article... Continue Reading... - Posted on Wednesday January 31, 2024

Tom Quad, Christ Church, Oxford University – image David BeardThe Oxford Experience summer school is held at Christ Church, Oxford. Participants stay in Christ Church and eat in the famous Dining Hall, that was the model for the Hall in the Harry Potter movies.This year there are twelve classes offered in archaeology.You can find the list of courses here… Continue Reading...

Tom Quad, Christ Church, Oxford University – image David BeardThe Oxford Experience summer school is held at Christ Church, Oxford. Participants stay in Christ Church and eat in the famous Dining Hall, that was the model for the Hall in the Harry Potter movies.This year there are twelve classes offered in archaeology.You can find the list of courses here… Continue Reading... - Posted on Monday January 29, 2024

‘It was killing fields as far as the eye can see’ … the Latin-inscribed slabs crossing the site of the battle, which features in the British Museum show Legion.Photograph: David Levene/The Guardian‘Their heads were nailed to the trees’: what was life – and death – like for Roman legionaries?It was the defeat that traumatised Rome, leaving 15,000 soldiers slaughtered in a German field. As a major show explores this horror and more, our writer finds traces of the fallen by a forest near the RhineIt is one of the most chilling passages in Roman literature. Germanicus, the emperor Tiberius’s nephew, is leading reprisals in the deeply forested areas east of the Rhine, when he decides to visit the scene of the catastrophic defeat, six years before, of his fellow Roman, Quinctilius Varus. The historian Tacitus describes what Germanicus finds: the ghastly human wreckage of a supposedly unbeatable army, deep in the Teutoburg Forest. “On the open ground,” he writes, “were whitening bones of men, as they had fled, or stood their ground, strewn everywhere or piled in heaps. Near lay fragments of weapons and limbs of horses, and also human heads, prominently nailed to trunks of trees.”Read the rest of this article... Continue Reading...

‘It was killing fields as far as the eye can see’ … the Latin-inscribed slabs crossing the site of the battle, which features in the British Museum show Legion.Photograph: David Levene/The Guardian‘Their heads were nailed to the trees’: what was life – and death – like for Roman legionaries?It was the defeat that traumatised Rome, leaving 15,000 soldiers slaughtered in a German field. As a major show explores this horror and more, our writer finds traces of the fallen by a forest near the RhineIt is one of the most chilling passages in Roman literature. Germanicus, the emperor Tiberius’s nephew, is leading reprisals in the deeply forested areas east of the Rhine, when he decides to visit the scene of the catastrophic defeat, six years before, of his fellow Roman, Quinctilius Varus. The historian Tacitus describes what Germanicus finds: the ghastly human wreckage of a supposedly unbeatable army, deep in the Teutoburg Forest. “On the open ground,” he writes, “were whitening bones of men, as they had fled, or stood their ground, strewn everywhere or piled in heaps. Near lay fragments of weapons and limbs of horses, and also human heads, prominently nailed to trunks of trees.”Read the rest of this article... Continue Reading... - Posted on Monday January 29, 2024

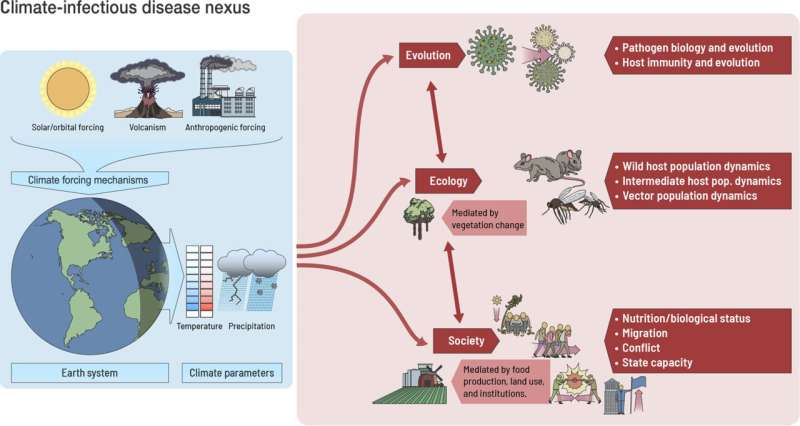

Schematic drawing of the relationship between climatic change and sociological, physical, and biological factors influencing infectious disease outbreaks.Credit: Science Advances (2024). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adk1033A team of geoscientists, Earth scientists and environmental scientists affiliated with several institutions in Germany, the U.S. and the Netherlands has found a link between cold snaps and pandemics during the Roman Empire.In their project, reported in the journal Science Advances, the group studied core samples taken from the seabed in the Gulf of Taranto and compared them with historical records.Researchers learn about climatic conditions in the distant past by analyzing sediment built up from river deposits. Tiny organisms that are sensitive to temperature, for example, respond differently to warm temperatures than to cold temperatures and often wind up in such sediment. Thus, the study of organic remains in sediment layers can reveal details of temperatures over a period of time.Read the rest of this article... Continue Reading...

Schematic drawing of the relationship between climatic change and sociological, physical, and biological factors influencing infectious disease outbreaks.Credit: Science Advances (2024). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adk1033A team of geoscientists, Earth scientists and environmental scientists affiliated with several institutions in Germany, the U.S. and the Netherlands has found a link between cold snaps and pandemics during the Roman Empire.In their project, reported in the journal Science Advances, the group studied core samples taken from the seabed in the Gulf of Taranto and compared them with historical records.Researchers learn about climatic conditions in the distant past by analyzing sediment built up from river deposits. Tiny organisms that are sensitive to temperature, for example, respond differently to warm temperatures than to cold temperatures and often wind up in such sediment. Thus, the study of organic remains in sediment layers can reveal details of temperatures over a period of time.Read the rest of this article... Continue Reading...

![]()

Archaeology and Egyptology in the 21st century

- Posted on Wednesday August 27, 2025

It’s been almost a year since I posted. A family crisis and intensive work have filled my time, but things are easing and I am intending to publish every two months going forward. In the last year I’ve been adapting to ArcGIS Pro, so expect some posts and videos about that in future. I’ve also been working on the Egypt Exploration Society’s Delta Survey Online web-map, which you can go and interact with at https://www.ees.ac.uk/our-cause/research/delta-survey.html. Just follow the last tab to the ‘Delta Survey Online’ (scroll down to the bottom of the page if you are on a handheld device) and view the data in the embed, or click through to the ArcGIS Online map to explore, analyse and export.

The Asyut Region Project

The location of the Gebel Asyut el-Gharbi in Middle Egypt. (British War Office Survey of Egypt 1:25000 scale map of Asyut, from the Center for Ancient Middle Eastern Landscapes (CAMEL), Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago).

In 2017-19 I worked on the Asyut Region Project, looking at the archive of David George Hogarth’s excavations in 1906-7 at Asyut. I continued this research independtly after the end of the project and a paper from this work has recently been published. My 2024 article in Interdisciplinary Egyptology, ‘Resurrecting the Archive: Revitalising records of Hogarth’s excavations in the Gebel Asyut el-Gharbi necropolis, Egypt 1906–1907’, proposes approximate locations for the tombs Hogarth excavated on the Gebel Asyut el-Gharbi in 1906-7, based on his sketch-map, the descriptions in his Notebook and Diary and some judicious satellite-imagery-based detective work (Pethen 2024). You can read all about it at https://doi.org/10.25365/integ.2025.v4.1.

During the course of this research and while working on my previous article on the Hogarth’s pottery corpus (Pethen 2021), I noted that it was possible to track Hogarth’s movement across the Gebel Asyut el-Gharbi from the combination of his Diary and Notebook entries and the approximate locations of the tombs he excavated. It was not possible to visualise the progress of the excavation in the published articles, but it can be visualised in an ArcGIS Story Map.

The sketch map of Hogarth’s excavations at the Gebel Asyut el-Gharbi. British Museum Dept of Egyptian and Assyrian Antiquities, Correspondence 1907 A-K, 321 (© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence).

Dating Hogarth’s tombs by discovery or excavation date

Before creating a Story Map showing how Hogarth moved across the Gebel between December 1906 and February 1907, it was necessary to cross-reference the records in Hogarth’s Notebook and Diary to determine when he first found each of the tombs in the sketch-map. I used the earliest dated reference to a tomb in either document. Given the somewhat variable nature of Hogarth’s recording (for more details of which see Pethen 2021; 2024), this means that the date associated with the tombs is sometimes the date that Hogath first noted the tomb, and sometimes the first day of the excavation. The table below shows the dates first associated with ... Continue Reading...

It’s been almost a year since I posted. A family crisis and intensive work have filled my time, but things are easing and I am intending to publish every two months going forward. In the last year I’ve been adapting to ArcGIS Pro, so expect some posts and videos about that in future. I’ve also been working on the Egypt Exploration Society’s Delta Survey Online web-map, which you can go and interact with at https://www.ees.ac.uk/our-cause/research/delta-survey.html. Just follow the last tab to the ‘Delta Survey Online’ (scroll down to the bottom of the page if you are on a handheld device) and view the data in the embed, or click through to the ArcGIS Online map to explore, analyse and export.

The Asyut Region Project

The location of the Gebel Asyut el-Gharbi in Middle Egypt. (British War Office Survey of Egypt 1:25000 scale map of Asyut, from the Center for Ancient Middle Eastern Landscapes (CAMEL), Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago).

In 2017-19 I worked on the Asyut Region Project, looking at the archive of David George Hogarth’s excavations in 1906-7 at Asyut. I continued this research independtly after the end of the project and a paper from this work has recently been published. My 2024 article in Interdisciplinary Egyptology, ‘Resurrecting the Archive: Revitalising records of Hogarth’s excavations in the Gebel Asyut el-Gharbi necropolis, Egypt 1906–1907’, proposes approximate locations for the tombs Hogarth excavated on the Gebel Asyut el-Gharbi in 1906-7, based on his sketch-map, the descriptions in his Notebook and Diary and some judicious satellite-imagery-based detective work (Pethen 2024). You can read all about it at https://doi.org/10.25365/integ.2025.v4.1.

During the course of this research and while working on my previous article on the Hogarth’s pottery corpus (Pethen 2021), I noted that it was possible to track Hogarth’s movement across the Gebel Asyut el-Gharbi from the combination of his Diary and Notebook entries and the approximate locations of the tombs he excavated. It was not possible to visualise the progress of the excavation in the published articles, but it can be visualised in an ArcGIS Story Map.

The sketch map of Hogarth’s excavations at the Gebel Asyut el-Gharbi. British Museum Dept of Egyptian and Assyrian Antiquities, Correspondence 1907 A-K, 321 (© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence).

Dating Hogarth’s tombs by discovery or excavation date

Before creating a Story Map showing how Hogarth moved across the Gebel between December 1906 and February 1907, it was necessary to cross-reference the records in Hogarth’s Notebook and Diary to determine when he first found each of the tombs in the sketch-map. I used the earliest dated reference to a tomb in either document. Given the somewhat variable nature of Hogarth’s recording (for more details of which see Pethen 2021; 2024), this means that the date associated with the tombs is sometimes the date that Hogath first noted the tomb, and sometimes the first day of the excavation. The table below shows the dates first associated with ... Continue Reading... - Posted on Wednesday September 25, 2024

In July’s post, I reviewed The Telegraph’s assertion that the Pitt-Rivers Museum had been ‘hiding’ objects that women were not supposed to see. You can find an archived version of the original Telegraph article here. The article is superficially about the exclusion of an object from public display (including digital display in collections online) to explicitly prevent a certain group (in this case women) from seeing that object. It’s main argument has been largely refuted in this article by the Pitt Rivers Museum, and in two threads about digital and in person access byMadeline Odent (@oldenoughtosay), on the platform formerly known as Twitter.

In my previous post, I looked at the misunderstandings about museums that underpinned The Telegraph’s article. A careful reading of the article reveals that neither women’s access to the Igbo mask, nor the somewhat more philosophically interesting subject of who should be able to access taboo or sensitive objects, is its real theme! It’s primary purpose is to denigrate the Pitt Rivers Museum’s policies on cultural sensitivity, and the decolonisation process of which they form a part. So far so boring and predictable, but what is interesting about this article are the methods it uses to manipulate the reader.

Reverse Outlining

To take a really close look at the Telegraph article, I printed it out and numbered the paragraphs. Then on the left side of the paper I noted the points of each paragraph, and on the right side, details that jumped out at me about how the article was written. If you want to see what that looks like, I’ve posted images of the results below. I have blurred the human remains in two of the images so those who do not wish to see are not accidentally exposed. Annoyingly, the final sentence of the article has strayed onto a fourth page, but it is functionally the end of the previous paragraph. For copyright purposes please note that I reproduce these images of the marked-up article here, without ‘alt-text’ of the article content, as a means to criticism and review. They are not meant for in-depth reading, but merely as a visual guide to how I analysed the article.

For those with an interest in academic writing techniques, I used a process known as ‘Reverse Outlining‘ in analysing the Telegraph article. If you want to see more about how it works, you can follow the previous link to Pat Thompson’s incredibly useful patter blog, or this article by Rachael Cayley.

First page of the reverse outlined Telegraph article. I have blurred the image of the tsantsa.

Second page of the reverse outlined Telegraph article.

Third page of the reverse outlined Telegraph article. I have blurred out the human remains in the photograph at the top.

The fourth page of the reverse outlined Telegraph article, only includes one sentence from the article.

Womens rights

The article is framed as an expose of a threat to women’s rights in the form of restrictions placed on the public display ... Continue Reading...

In July’s post, I reviewed The Telegraph’s assertion that the Pitt-Rivers Museum had been ‘hiding’ objects that women were not supposed to see. You can find an archived version of the original Telegraph article here. The article is superficially about the exclusion of an object from public display (including digital display in collections online) to explicitly prevent a certain group (in this case women) from seeing that object. It’s main argument has been largely refuted in this article by the Pitt Rivers Museum, and in two threads about digital and in person access byMadeline Odent (@oldenoughtosay), on the platform formerly known as Twitter.

In my previous post, I looked at the misunderstandings about museums that underpinned The Telegraph’s article. A careful reading of the article reveals that neither women’s access to the Igbo mask, nor the somewhat more philosophically interesting subject of who should be able to access taboo or sensitive objects, is its real theme! It’s primary purpose is to denigrate the Pitt Rivers Museum’s policies on cultural sensitivity, and the decolonisation process of which they form a part. So far so boring and predictable, but what is interesting about this article are the methods it uses to manipulate the reader.

Reverse Outlining

To take a really close look at the Telegraph article, I printed it out and numbered the paragraphs. Then on the left side of the paper I noted the points of each paragraph, and on the right side, details that jumped out at me about how the article was written. If you want to see what that looks like, I’ve posted images of the results below. I have blurred the human remains in two of the images so those who do not wish to see are not accidentally exposed. Annoyingly, the final sentence of the article has strayed onto a fourth page, but it is functionally the end of the previous paragraph. For copyright purposes please note that I reproduce these images of the marked-up article here, without ‘alt-text’ of the article content, as a means to criticism and review. They are not meant for in-depth reading, but merely as a visual guide to how I analysed the article.

For those with an interest in academic writing techniques, I used a process known as ‘Reverse Outlining‘ in analysing the Telegraph article. If you want to see more about how it works, you can follow the previous link to Pat Thompson’s incredibly useful patter blog, or this article by Rachael Cayley.

First page of the reverse outlined Telegraph article. I have blurred the image of the tsantsa.

Second page of the reverse outlined Telegraph article.

Third page of the reverse outlined Telegraph article. I have blurred out the human remains in the photograph at the top.

The fourth page of the reverse outlined Telegraph article, only includes one sentence from the article.

Womens rights

The article is framed as an expose of a threat to women’s rights in the form of restrictions placed on the public display ... Continue Reading... - Posted on Wednesday August 28, 2024

In my previous post, I discussed a Telegraph article, published on 17 June 2024 which criticised the Pitt Rivers Museum for ‘hiding’ objects that women were not supposed to see. You can find an archived version of the original Telegraph article here. While Madeline Odent (@oldenoughtosay) on Twitter and the Pitt Rivers Museum (in this article) rebutted most of the claims made by the Telegraph, it would not have been nearly as effective without certain gross misunderstandings of what museums are and how they work. I previously wrote here about how the redisplay of certain Wellcome Museum galleries was subject to similar misunderstandings in 2022, but it seems these misunderstandings continue. They may even be more intense in Wunderkammer-style museum, like the Pitt Rivers, which is as Madeline Odent puts it, ‘somewhat unusual among modern museums in that it has largely kept to its Victorian roots of ‘cram as many artefacts as possible into each display case’. If you’re unfamiliar with the PRM, it’s somewhat unusual among modern museums in that it has largely kept to its Victorian roots of ‘cram as many artefacts as possible into each display case’— madeline boOoOoOodent (@oldenoughtosay) June 25, 2024 Madeline Odent’s thread about visiting the Pitt-Rivers Museum, with her succinct description of its ‘Wunderkammer-style’. What is a museum? Museums, especially archaeological museums, often combine the function of object warehouse, educational institute, and art gallery. As I described in my post about the Wellcome Museum, the latter two functions are what we experience when we visit the museum galleries, or an exhibition of objects from the museum (either in the same building or elsewhere). The publicly open galleries and exhibitions do not constitute the whole Museum. They are simply the part of the museum that is prepared for public visitation with carefully curated objects and relevant signage. This is more obvious when we visit a museum with a limited number of artefacts carefully displayed, but even then I suspect many people assume that that which is on display constitutes the entire museum. In this respect, the Wunderkammer-style of the Pitt Rivers, is a disadvantage, because the very large number of items on display itself suggests that the entire collection is visible. In fact, the visible artefacts in publicly open galleries and exhibition spaces only ever constitute a relatively small proportion of any museum’s holdings! The Igbo mask, the focus of the Telegraph’s article, has not been ‘hidden’. It was never on display, along with much of the rest of the collection! The Collection The majority (exact proportions vary) of any museum’s holdings are held in storage. Together the objects in storage and those on display are described as the museum’s collection. Some of these objects are not on display because they are fragile or would be at risk in some way. Some are sufficiently similar to objects on display that including them would clutter display cases without adding further interest or value. Others are simply extremely boring to any but dedicated specialists. The holdings ... Continue Reading...

- Posted on Wednesday July 31, 2024

‘Regular readers will know that I’m interested in both public misunderstandings of archaeology and heritage and ‘Wunderkammer‘ style museums. So I was interested when on 17 June 2024, the Telegraph newspaper published an article critical of the Pitt Rivers Museum. The reaction to this on Twitter and in this rebuttal by the museum revealed that the article demonstrated both significant misunderstandings about the nature and purpose of museums, and how those misunderstandings are politicised.

Now, do some photos have sensitivity warnings? Sure. When you visit the site, you get a pop up, and you can opt in OR OUT of the warnings. If you opt in, you can click thru to see something with a warning. For a small number, there’s no image. Here’s what that looks like. pic.twitter.com/YjlN2Y0m7i— madeline odent (@oldenoughtosay) June 19, 2024

Sensitivity warnings in the online catalogue, including one example where the image is not available to the public. (Tweet by @oldenoughtosay)

Repatriation?

As an aside, it’s worth noting that I am not going to engage here with the question of repatriation of objects. That is a very complex and important issue and there’s insufficient space here to do it justice. My focus here is public understanding of what museums do and are, where misunderstandings lie and how those misunderstandings can be corrected or exploited.

Hiding masks?

The Telegraph article was entitled “University of Oxford museum hides African mask that ‘must not be seen by women’”. You can find an archived version of the original Telegraph article here. It asserted that the museum had removed a Nigerian Igbo mask from display, and photos of it from the online catalogue because the culture of origin forbade women from seeing it. The article then linked these actions with a ‘decolonization process’ (the quotation marks are original to the article), that involved removal of the museum’s tsantsa (also known as ‘Shrunken heads’) and the addition of cultural sensitivity warnings, all resulting from the museum’s response to the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020.

Truth or fiction?

This swift rebuttal from the Pitt Rivers Museum and some investigative tweeting by Madeline Odent (@oldenoughtosay) revealed that the core claims of the Telegraph article were largely misunderstandings of both general museology and specific museum policy. To summarise, the Igbo mask in question has not been removed from display because it never was on display; a large proportion of the collection has yet to be photographed; some photographs have sensitivity warnings (image above right from Madeline Odent’s thread) and a very few are not available to view online; but researchers are welcome to visit and no one has ever been denied access to the mask.

Pure coincidence that we just posted about this earlier. The curtains are to protect the delicate feathers from being damaged by too much light. https://t.co/PKZqBSXHX7— Pitt Rivers Museum (@Pitt_Rivers) June 25, 2024

Pitt Rivers Museum on Twitter confirming that the curtain was added for conservation reasons.

Madeline Odent followed up her initial thread with this live-tweeted visit to the Pitt Rivers Museum, to test the idea that significant changes ... Continue Reading...

‘Regular readers will know that I’m interested in both public misunderstandings of archaeology and heritage and ‘Wunderkammer‘ style museums. So I was interested when on 17 June 2024, the Telegraph newspaper published an article critical of the Pitt Rivers Museum. The reaction to this on Twitter and in this rebuttal by the museum revealed that the article demonstrated both significant misunderstandings about the nature and purpose of museums, and how those misunderstandings are politicised.

Now, do some photos have sensitivity warnings? Sure. When you visit the site, you get a pop up, and you can opt in OR OUT of the warnings. If you opt in, you can click thru to see something with a warning. For a small number, there’s no image. Here’s what that looks like. pic.twitter.com/YjlN2Y0m7i— madeline odent (@oldenoughtosay) June 19, 2024

Sensitivity warnings in the online catalogue, including one example where the image is not available to the public. (Tweet by @oldenoughtosay)

Repatriation?

As an aside, it’s worth noting that I am not going to engage here with the question of repatriation of objects. That is a very complex and important issue and there’s insufficient space here to do it justice. My focus here is public understanding of what museums do and are, where misunderstandings lie and how those misunderstandings can be corrected or exploited.

Hiding masks?

The Telegraph article was entitled “University of Oxford museum hides African mask that ‘must not be seen by women’”. You can find an archived version of the original Telegraph article here. It asserted that the museum had removed a Nigerian Igbo mask from display, and photos of it from the online catalogue because the culture of origin forbade women from seeing it. The article then linked these actions with a ‘decolonization process’ (the quotation marks are original to the article), that involved removal of the museum’s tsantsa (also known as ‘Shrunken heads’) and the addition of cultural sensitivity warnings, all resulting from the museum’s response to the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020.

Truth or fiction?

This swift rebuttal from the Pitt Rivers Museum and some investigative tweeting by Madeline Odent (@oldenoughtosay) revealed that the core claims of the Telegraph article were largely misunderstandings of both general museology and specific museum policy. To summarise, the Igbo mask in question has not been removed from display because it never was on display; a large proportion of the collection has yet to be photographed; some photographs have sensitivity warnings (image above right from Madeline Odent’s thread) and a very few are not available to view online; but researchers are welcome to visit and no one has ever been denied access to the mask.

Pure coincidence that we just posted about this earlier. The curtains are to protect the delicate feathers from being damaged by too much light. https://t.co/PKZqBSXHX7— Pitt Rivers Museum (@Pitt_Rivers) June 25, 2024

Pitt Rivers Museum on Twitter confirming that the curtain was added for conservation reasons.

Madeline Odent followed up her initial thread with this live-tweeted visit to the Pitt Rivers Museum, to test the idea that significant changes ... Continue Reading... - Posted on Wednesday April 24, 2024

Mastabas in the Eastern Cemetery, with the Great Pyramid of Khufu (rear right); the pyramid of Khafre (rear, left) and the pyramid of Khufu’s Queen Henutsen (rear, centre) behind. A small chapel is visible in the ‘street’ between the mastabas in the foreground, with the denuded edge of mastaba G7430 behind it. To the left is the north edge of mastaba G7520. (Author photograph February 2024).

The Eastern Cemetery

East of the Great Pyramid, arranged in careful blocks, like a suburb of the dead, are a series of large mastaba (bench) tombs belonging to the nobles of Khufu’s court. The format for these tombs was relatively simple, the masonry ‘bench’ structure contained the offering places and, later, the more extensive tomb chapels, in which the cult of the dead was celebrated. The deceased with their grave goods were buried in subterranean tomb chambers, accessed via various burial shafts, concealed within the masonry structure. Most of these mastabas are closed to the public, although a rotating series of more interesting, well-preserved, and decorated tombs are accessible as part of the Giza Plateau ticket. (These include but are not limited to; G6020 Iymery; G7101 Qar; G7102 Idu; G7130-40 Khufukhaf; G7060 Nefermaat; G7070 Senefrukaef; Lepsius 53, Seshemnefer IV.) The tomb of Meresankh III is an exception to this rule. It is accessible only with a separate ticket and (after recent conservation) is almost always open.

Google Maps satellite image of the Great Pyramid and the Eastern Cemetery. The mastabas of the Eastern cemetery appear as rectangular shapes, with the dark squares of the tomb shafts clearly visible cutting through the masonry. The ‘Tomb of Mers Ankh’ is correctly located. The entrance is on the eastern side of the mastaba, to the right of the red pin.

The family of Meresankh III (centre), her mother Hetepheres II (left) and her son Nebemabkhet, who was later a vizier (right). Another probable son, Khenterka is shown as a child in front of Meresankh III, holding a lotus flower and a bird.

Visiting Meresankh III’s Mastaba G7530-G7540

Meresankh III’s tomb is mastaba G7530-7540, roughly in the middle of the Eastern Cemetery, between the Great Pyramid and the valley. Surprisingly, the Google maps Tomb of Mers Ankh pin is almost exactly correct, just to the left of the subterranean tomb entrance (previous image). For those with small folk, it is also quite child-friendly. The scenes and statues are interesting and retain some of the paint, the burial chamber is easily accessible and, the tomb isn’t too large for a five-year-old attention span. Plus, for those with Disney-obsessed kids, she’s an actual bonafide princess and Queen!

Prince Kawab, eldest son of Khufu and Meresankh III’s father, is the largest of any figure in her tomb. (Author photograph).

Meresankh III

Meresankh III was a granddaughter of Khufu, builder of the Great Pyramid, and wife of Pharaoh Khafre. Her Father, the eldest son of Khufu, Prince Kawab, is featured on the east wall of the first chamber. Her mother, Hetepheres II appears several times, and her son ... Continue Reading...

Mastabas in the Eastern Cemetery, with the Great Pyramid of Khufu (rear right); the pyramid of Khafre (rear, left) and the pyramid of Khufu’s Queen Henutsen (rear, centre) behind. A small chapel is visible in the ‘street’ between the mastabas in the foreground, with the denuded edge of mastaba G7430 behind it. To the left is the north edge of mastaba G7520. (Author photograph February 2024).

The Eastern Cemetery

East of the Great Pyramid, arranged in careful blocks, like a suburb of the dead, are a series of large mastaba (bench) tombs belonging to the nobles of Khufu’s court. The format for these tombs was relatively simple, the masonry ‘bench’ structure contained the offering places and, later, the more extensive tomb chapels, in which the cult of the dead was celebrated. The deceased with their grave goods were buried in subterranean tomb chambers, accessed via various burial shafts, concealed within the masonry structure. Most of these mastabas are closed to the public, although a rotating series of more interesting, well-preserved, and decorated tombs are accessible as part of the Giza Plateau ticket. (These include but are not limited to; G6020 Iymery; G7101 Qar; G7102 Idu; G7130-40 Khufukhaf; G7060 Nefermaat; G7070 Senefrukaef; Lepsius 53, Seshemnefer IV.) The tomb of Meresankh III is an exception to this rule. It is accessible only with a separate ticket and (after recent conservation) is almost always open.

Google Maps satellite image of the Great Pyramid and the Eastern Cemetery. The mastabas of the Eastern cemetery appear as rectangular shapes, with the dark squares of the tomb shafts clearly visible cutting through the masonry. The ‘Tomb of Mers Ankh’ is correctly located. The entrance is on the eastern side of the mastaba, to the right of the red pin.

The family of Meresankh III (centre), her mother Hetepheres II (left) and her son Nebemabkhet, who was later a vizier (right). Another probable son, Khenterka is shown as a child in front of Meresankh III, holding a lotus flower and a bird.

Visiting Meresankh III’s Mastaba G7530-G7540

Meresankh III’s tomb is mastaba G7530-7540, roughly in the middle of the Eastern Cemetery, between the Great Pyramid and the valley. Surprisingly, the Google maps Tomb of Mers Ankh pin is almost exactly correct, just to the left of the subterranean tomb entrance (previous image). For those with small folk, it is also quite child-friendly. The scenes and statues are interesting and retain some of the paint, the burial chamber is easily accessible and, the tomb isn’t too large for a five-year-old attention span. Plus, for those with Disney-obsessed kids, she’s an actual bonafide princess and Queen!

Prince Kawab, eldest son of Khufu and Meresankh III’s father, is the largest of any figure in her tomb. (Author photograph).

Meresankh III

Meresankh III was a granddaughter of Khufu, builder of the Great Pyramid, and wife of Pharaoh Khafre. Her Father, the eldest son of Khufu, Prince Kawab, is featured on the east wall of the first chamber. Her mother, Hetepheres II appears several times, and her son ... Continue Reading...

![]()

![]()